Methodology

Research approaches

Research approach developed in practice

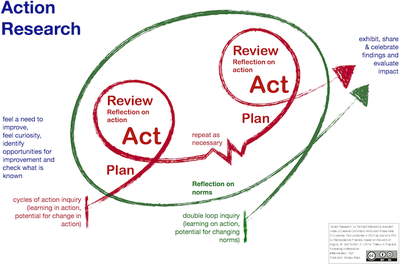

The design of software, resources and systems I have developed has been undertaken in the context of a series of research projects. The inquiry paradigm of these projects started with creative curriculum development in the early part of my career and later became overlaid with a more explicitly collaborative action research approach (Lewin 1973, 205-6; Argyris and Schön 1978), within and on the education system itself. My mature visualisation of this approach is shown in the following figure, developed as a wall poster:

Figure 2: A model of action research

This paradigm is not without its problems, as Somekh and Zeichner put it:

Action research, as a proposition, has discursive power because it embodies a collision of terms. In generating research knowledge and improving social action at the same time, action research challenges the normative values of two distinct ways of being – that of the scholar and the activist.

(Somekh & Zeichner 2009, p5)

This notion of two ways of being has specific attraction for the designer & developer in me, who loves to make and do, not simply think and reflect. Thus it has been natural for me to engage in the iterative and cyclical phases of action research - planning, acting, reviewing and with growing awareness of its meaning. Planning has included collaboration with experts, practitioners and learners inspired to envision the potential for innovation with technology in education. Acting has ranged from coding programs, creating CD-ROMs, designing web-sites, configuring online communities, teaching, facilitation, marketing of courses and direction of large teams of colleagues. Reviewing has involved empirical data collection methods including observation, interview, focus group, survey and videography. This has been followed by analysis of the quantitative & qualitative data collected and subsequent interpretation to develop conclusions which inform the next cycle of inquiry. Double loop learning, the identification and critical questioning of governing variables (Argyris and Schön 1978), has been common throughout as I and collaborators bloodied ourselves confronting the inherent conservatism of educational practices, institutions and frameworks whilst making sense of technology innovations.

This action research approach and all these methods have been employed in my practice as part of the many research and development projects undertaken, and they are described and exemplified in the section Methodologies developed in Practice.

Research approach to the dissertation

When setting out to develop this dissertation, I decided on a reflective methodological approach (Dewey 1933, Schön 1983) and related methods to construct it, but, keeping true to my practice of design and what drives me, the design and development of a resource in the shape of a web site was a vital element. The steps taken to arrive at the substance and presentation of my dissertation are discussed in the section Methodology for this dissertation.

This web-site can be found at http://phd.richardmillwood.net

Values driving the research

The research and development I have been engaged in has always been values-driven, in a nutshell 'to change the world for the better'. Over time these values have developed, but they clearly indicate a subjective viewpoint, and thus run the risk of introducing bias and overlooking issues. Friedman et al explain that the motivation for such values cannot be purely empirical:

"values cannot be motivated only by an empirical account of the external world, but depend substantively on the interests and desires of human beings within a cultural milieu"

(Friedman et al 2006, 2)

Friedman et al explain the background to a values-based approach (Friedman et al 2006, 2) and then go on to exemplify these, see table 2: Human Values (with Ethical Import) Often Implicated in System Design (Friedman et al 2006, 17). These tend towards individual rights of users rather than responsibilities, in a context of designers and users. The authors also note that the set is not comprehensive.

Table 2: Human Values (with Ethical Import) Often Implicated in System Design

|

Human Value |

Definition |

|

Human Welfare |

Refers to people's physical, material, and psychological well-being |

|

Ownership and Property |

Refers to a right to possess an object (or information), use it, manage it, derive income from it, and bequeath it |

|

Privacy |

Refers to a claim, an entitlement, or a right of an individual to determine what information about himself or herself can be communicated to others |

|

Freedom From Bias |

Refers to systematic unfairness perpetrated on individuals or groups, including pre-existing social bias, technical bias, and emergent social bias |

|

Universal Usability |

Refers to making all people successful users of information technology |

|

Trust |

Refers to expectations that exist between people who can experience good will, extend good will toward others, feel vulnerable, and experience betrayal |

|

Autonomy |

Refers to people's ability to decide, plan, and act in ways that they believe will help them to achieve their goals |

|

Informed Consent |

Refers to garnering people's agreement, encompassing criteria of disclosure and comprehension (for 'informed') and voluntariness, competence, and agreement (for 'consent') |

|

Accountability |

Refers to the properties that ensures that the actions of a person, people, or institution may be traced uniquely to the person, people, or institution |

|

Courtesy |

Refers to treating people with politeness and consideration |

|

Identity |

Refers to people's understanding of who they are over time, embracing both continuity and discontinuity over time |

|

Calmness |

Refers to a peaceful and composed psychological state |

|

Environmental Sustainability |

Refers to sustaining ecosystems such that they meet the needs of the present without compromising future generations |

The values I identified diverge and are a subset of theirs, and focus on responsibilities on both designers and users as partners in design.

The approach I have taken here has been to identify the key values that have driven my work, critically recognise the risks whilst maintaining a moral & ethical perspective and where possible, make a connection with Friedman et al's set .

Collaboration

This value is related to Friedman et al's 'Trust' and 'Autonomy'. All the research and development I have engaged in recognises that collaboration is essential. The positive features for me are:

- a continuing dialogue of critical friendship;

- the benefit of diverse strengths and perspectives;

- where possible, the democratic involvement of beneficiaries and stakeholders to improve ideas, evaluation and uptake.

This follows the approach of Cooperative Inquiry (Heron and Reason 2006, 144-152) which recognises an approach where people with similar concerns work together to make sense of their world, developing creative ways of considering problems and learning how to bring about change in things that they want to improve.

Heron and Reason (ibid.) identify two participatory principles:

- epistemic participation, “propositional knowledge that is the outcome of the research is grounded by the researchers in their own experiential knowledge”; and

- political participation, “research subjects have the basic human right to participate fully in designing the research that intends to gather knowledge about them.”

This approach rejects the division of practitioner and researcher into different roles. Instead, it sees inquiry as a social process that is emancipatory, in that allows those who participate to be considered both as researchers and as themselves.

Boylorn (2008) identifies:

Participants as co-researchers refers to a participatory method of research that situates participants as joint contributors and investigators to the findings of a research project. This qualitative research approach validates and privileges the experiences of participants, making them experts and therefore co-researchers and collaborators in the process of gathering and interpreting data.

(Boylorn 2008)

One risk has been an 'averaging' of creative ideas to achieve consensus, but on reflecting back over my practice, this has rarely prevented innovation. Another relates to the relative lack of expertise, which may limit the participant's ability to contribute. This is particularly so when working with students, but the benefits can be unexpected. With higher expectations, young people often step up to meet them, as discovered in the context of the [P6] Étui project, where we invited children to act as researchers to evaluate toys and their design.

Critical friendship in research

This is related to Friedman et al's Freedom from bias'. It has been vital throughout my practice to invite colleagues to comment on plans, activity and analysis.

Costa and Kallick (1993) define a critical friend as:

a trusted person who asks provocative questions, provides data to be examined through another lens, and offers critiques of a person’s work as a friend. A critical friend takes the time to fully understand the context of the work presented and the outcomes that the person or group is working toward. The friend is an advocate for the success of that work.

(Costa and Kallick 1993)

I have valued many critical friends, listed in the Portfolio and acting as a critical friend to many colleagues, and so this has been an important value in my practice.

The risks include the potential for breakdown of relationship and trust, as Cost and Kallick (1993) put it:

Because the concept of critique often carries negative baggage, a critical friendship requires trust and a formal process. Many people equate critique with judgment, and when someone offers criticism, they brace themselves for negative comments.

(Costa and Kallick 1993)

Social justice

This is related to Friedman et al's 'Freedom from bias'. The idea that research and development might address inequalities of opportunity in society through education has been central to my practice. I have tried to follow Light and Luckin's (2008) proposal that we :

address the way in which TEL and user-centred design approaches can offer learners an experience that meets their individual needs and addresses the needs of minority groups as well as the majority

(Light and Luckin 2008, 30)

Thus I have avoided methodologies such as experimental design, which favour one group over another through a treatment group and a control group and to favour more participative and naturalistic approaches using qualitative methods to evaluate outcomes. In the design process it has meant paying attention to diversity, culture and gender issues and making positive efforts in the design of innovations to address these. This has occasionally needed to counter technology-led innovation, which so often simply addresses 'normal' users.

The risk is that in some cases, a compromise has been needed between exploring new designs and addressing accessibility, whilst maintaining a moral and ethical view of the issue.

Transparency and participation

This could be the opposite of Friedman et al's 'Privacy'. My first software development work as a full-time researcher at Computers in the Curriculum in 1980 obliged me to work closely and to be led in pedagogical issues by teacher-groups and individual teachers leading on items of software. This demanded a transparency in planning and participation in design which I came to value. The returns were a growing awareness of practising teachers' knowledge and concerns combined with a practical means to deliver on the values of social justice. This in turn led to design and development criteria informed by my practice working with the teachers. In later projects, especially at Ultralab in the 90s this approach was extended to include school students as 'co-researchers', inviting them to understand the goals of our developments and to contribute at every level.

The risks relate to privacy and safety for participants, which can be undermined with too much transparency.

Delight

There is no equivalent to delight in Friedman et al's analysis. The intuitive idea that delight was essential to successful learning was a central tenet in Ultralab in the 90s, encouraging the team to develop software for learning with features intended to inspire delight in learners. Hargreaves analysis of teacher types as 'lion-tamer', 'entertainer' and 'new romantic' (Hargreaves 1992, 163) had prepared me for considering the affective nature of learning, but it wasn't until 2006 that I realised how much tacit knowledge had been developed by myself and colleagues to support delight as a value in design. The demands of articulating this fully in developing and presenting a television programme on well-being in schools for the Teachers' TV's School Matters series (Millwood 2007), helped me to recognise the nuanced detail of the concept and how deeply it had become key to my design and development practice. John Heron (Heron 1992, 122) theorises that delight may be experienced in multiple ways: 'appreciation' arising from a love of aesthetic form, 'interest' from a love of knowledge and 'zest' from a love of action. These delights are individual in nature, so I extended this analysis (Millwood 2008a) to propose three delights that are derived in association with other people: 'conviviality' from a love of company, 'recognition' from the love of achievement and 'controversy' from a love of dissent. All six of these delights have become important guides to effectiveness in my practice of designing educational experiences.

The risks in this value relate mostly to the diminution of delight and its confusion with 'fun', so often considered to be in opposition to the hard work that learning demands and thus a distraction.

Ethical issues

With the breadth of research & development undertaken throughout my practice, there have been a full range of ethical issues confronted. Particularly relevant have been issues of privacy and data protection with regard to minors, particularly as we developed large scale action research with school-aged children and in online environments. Measures to ensure appropriate ethical practice in the projects undertaken have been dealt with through the arrangements in place with my employers, the participants and their host organisations where relevant, but in some cases these had to be developed further in the context of new risks posed by the use of online technology and visual media.

In developing this dissertation, the main ethical concern has been to obtain the informed consent of colleagues I have described in the Portfolio. This has been done through invitation to review the materials and respond - all those who are still living have been kind enough to provide that. It has been essential to write about others, even though this dissertation is about my thesis and my practice, since:

writing the Self without acknowledging the Other is itself a violent (symbolic) act against the ethical condition that comes with being human.

(Roth 2009)

Thus, since so much of the practice I have engaged in has involved collaboration, it would be ethically unreasonable not to explain others' contribution to the thesis outlined in this dissertation.

(Words: 2948 )

Methodology developed in practice

Research approaches in practice

Design & development

The key approach in my practice has been the design and development of educational software, multimedia resources, systems and ultimately courses. This design approach has been in a context where new technology offers new and unknown opportunities and despite disquiet about technology-led approaches, has inspired creativity and innovation in my practice. The key to this research approach has been a combination of developing design methodology and rigorous evaluation in real-world contexts. In this sense, I have been unconsciously engaged in a 'design science' approach as discussed in the Theoretical and Conceptual Framework section of this dissertation.

Participant action research

As my work developed, I became increasingly conscious that I was developing a participant action research approach (Denzin and Lincoln 2005, 33-34) to complement design & development. This was the result of a growing interest and opportunity to design courses, degree programmes and ultimately secondary (Notschool.net project) and higher education organisation ([P9] Ultraversity project). In each case the concept of co-research with students became ever more explicit.

Specific Methods Used

Prototyping, iterative development and field testing

In developing new interactive educational software, an early discovery was that the traditional waterfall method (Bell and Thayer 1976), of identification of user needs followed by specification, implementation and testing, would not work. Participants (including myself) in the design process were discovering new needs, had little ability to specify unknown designs offering new practices and found themselves learning through the process of development in an 'expansive' sense (Engstrom 1999). A further complication in practice was that the computers in use had a range of features and capabilities and the design team would often have diverse understandings of what could be achieved. So the method employed was of prototyping initial ideas to produce a working design, not fully debugged nor complete, to inform the next steps and inspire further invention.

Prototyping was only the beginning of course, and was followed by cycles of development and field testing, often in classrooms by the teacher participants in the design and development process, whose understanding was also growing. Alongside the successive improvement in the software itself, there was a parallel and important task to develop the teachers' and students' guidance material which underwent a similar process.

As Mor puts it:

The design element in a design study may refer to the pedagogy, the activity, or the tools used. In some cases, the researchers will focus on iterative refinement of the educational design while keeping the tools fixed, whereas in others they may highlight the tools, applying a free-flowing approach to the activities. In yet others they will aspire to achieve a coherent and comprehensive design of the activity system as a whole.

(Mor 2010, 27)

Analysis of software designs

Frequently in the design process, a failure in use would be identified in broad terms - a teacher or student would report that some aspect was unclear, difficult to use or simply baffling. At this point it was important to analyse the software design (and the practice) to discover where improvement needed to be made. At first this was done informally and with tacit knowledge of 'what works', but this task was improved to make use of insights from the worlds of visual design and from human computer interface. The input from visual design and cognition theory (Marr 1982, Scrivener 1984, Gregory 1966) offered clarity about the simplest ideas of placement and the overlapping of graphical elements on the screen, the treatment of 'white space', typography and combinations of colours. The input from human computer interface theory was primarily from Donald Norman's Four Stages of User Activity (Norman 1983b), regarding the task analysis of operating equipment. We designed our own interpretation of this model to guide colleagues in our team - An Analysis of a Single Interaction (Millwood and Riley 1988), but oriented to operating a piece of educational software.

Online and interactive questionnaire surveys

In later practice, relating to the development of courses and self-evaluation, surveys that directly questioned participants became an additional method used (Lodico et al 2010, 12). The advent of low-cost online surveys, which also gave the researcher (academic or participant) an immediate and easily repeated summary analysis, meant this became an important method. I engaged in methodological development, writing new software to take advantage of the particular strengths of interactive designs. The strengths are that instead of using coding systems, letters or numerical values to rank or select choices, this can be achieved through interactive objects and sliders, building on kinaesthetic and visual thinking of respondents to help them more directly make the judgements about an issue being surveyed.The first venture in this direction came in the design of Making Choices (Millwood 1993), a tool for modelling decisions by interactively dragging choices into rank order and the COGs passport (Millwood 2004), a tool for transition between primary and secondary schooling. COGS helped learners evaluate their competencies by dragging elements in a geometric design. This survey method was developed most recently in the design of interactive learning needs analysis for health professionals and volunteers in the charity Macmillan Cancer Support.

Videography

In several projects, understanding the holistic context and seeing the detailed activity became important. In these cases, making video of the activity or of the discussion to evaluate it was employed, although this could prove challenging to access and analyse (Jewitt 2012). Shrum et al describe the 'fluid wall' and the 'videoactive context' to emphasize that (a) the camera is an actor, and (b) both behaviour and observation occur in both directions -- in front of and behind the camera (Shrum et al 2005). These notions have been frequently employed for projects in which I have been active to explore digital creativity with children.

In some cases, the video was transcribed and the transcription added to the video as a 'text track' which was searchable. Added value could be obtained by adding text tracks for chapters and for keyword analysis, permitting the video to be used as the vehicle for exploration and dissemination of research findings, not simply the data gathered. ( [P9] Ultraversity Project)

Although lowering of costs of equipment, media and the labour necessary to process have made this an attractive option, there are drawbacks associated with the quantity of data generated and the difficulties of processing, but these are offset in many cases by the direct and rich way in which knowledge of the research context can be communicated.

Structured Interview

In creating innovation in higher education, it became important to evaluate the experience of students and tutors in greater depth. In these cases we developed interview frameworks, conducted the interviews, recorded the audio transcribed and then employed an interpretive phenomenological analysis (Smith et al. 2009) to the data to discover in a grounded sense, the key themes of their response to our innovations (Millwood and Powell, 2009). These methods were particularly helpful in identifying conceptual knowledge in novel contexts offered by technology, although limited in reliability due to modest sample sizes and the potential for researcher bias (Brocki & Wearden 2006 101).

(Words: 1305 )

Methodology for this dissertation

Philosophical Approach – Pragmatism

The philosophical approach of Pragmatism - that the function of thought is as an instrument or tool for prediction, action, and problem solving (Peirce 1935; James 1898) - has inspired my work and guided the production of the thesis. The analyses are essentially thoughts expressed in a form that enables them to guide action in the design process. An influentual development from Pragmatism that informed my approach is that of Symbolic Interactionism (Mead 1934) - that people act on things based on the meaning those things have for them; and these meanings are arrived at through social interaction and modified through interpretation. Mead proposed that the true test of any theory was that "It was useful in solving complex social problems" (Griffin 2006, 59) and this has guided me to develop and defend the analyses in my thesis by gathering my work practice, discovering those aspects which have made the greatest contribution and attempting to link them to the thesis through the development of a hypertextual dissertation web site, before creating the paper document.

Methodological Approach – Autoethnography

Although it is clear that the approach I have taken is of autoethnography, there are variants, and my approach has been closest to that defined by Ellis - “research, writing, story, and method that connect the autobiographical and personal to the cultural, social, and political” (Ellis 2004, xix). Although I set out to describe and look critically at my experience, there is also the deliberate attempt to find theory in this dissertation, and a move from my tacit theories to those articulated in the analyses, [A1], [A2] and [A3], published with this dissertation, where the intent is to provide reliable tools to other designers. I hope that this desire and the positive outcomes of much of the practice I have been engaged in will counter the criticisms levelled at auto-ethnographers as "unscientific, or only exploratory, or subjective" (Denzin and Lincoln 2005, 8).

Bias

Autoethnographic approaches are criticised:

for being biased, navel-gazing, self-absorbed, or emotionally incontinent, and for hijacking traditional ethnographic purposes and scholarly contributions

(Maréchal 2010, 45)

I would counter this concern with the observation that this dissertation is not concerned with simply depicting my practice, but with setting out an abstract and theoretical thesis which is justified by the account of practice. In this sense, the autoethnographic approach recognises the capacity for bias, but is concerned to be faithful and productive to the author's thinking and experience. Triangulation of this account comes from the evidence cited in the Claim section.

Evaluating autoethnographic work

The five factors described by Richardson (2000, 15-16) for evaluating such work are used here to justify my position, and for you the reader to judge my success as set out in table 3.

Table 3: Richardson's factors for evaluating autoethonographic work (Richardson 2000, 15-16)

| Factor | Response for this dissertation |

|---|---|

|

Substantive contribution Does the piece contribute to our understanding of social life? |

Taken as a whole, the portfolio explains the career of an individual (me) in times of change in education as technology matured and became ubiquitous, changing the face of education. I have related my development to the more influential people that I worked with, but recognise a huge number of others that made my work and learning possible. |

|

Aesthetic merit Does this piece succeed aesthetically? Is the text artistically shaped, satisfyingly complex, and not boring? |

This dissertation is also presented as a designed web-site (http://phd.richardmillwood.net/), attempting to please aesthetically. |

|

Reflexivity How did the author come to write this text? How has the author’s subjectivity been both a producer and a product of this text? |

In reviewing all my professional practice to prepare for this dissertation, I have systematically developed reflective written material for the most significant events. I have constructed identity and place in my life's work through this process and this has made me a product of this text. |

|

Impactfulness Does this affect me emotionally and/or intellectually? Does it generate new questions or move me to action? |

The demand to articulate more clearly my theoretical perspectives and find coherence in them has provided many questions. Impact has also been seen in the outcomes of my practice. |

|

Expresses a reality Does this text embody a fleshed out sense of lived experience? |

By including my employment, education and professional responsibilities I have tried to show a complete career. Although I could have included much more personal matters of family and relationship, the reflective section in my portfolio about people I have worked with will, I hope, illuminate how I have been humanly influenced. |

Specific method used to develop the dissertation

Designing the dissertation web site

From the outset, the processes of gathering, categorising, reflecting, selecting and presenting were identified as knowledge and information management tasks, which from the author's perspective demanded the use of a content management system (CMS). The practice of designing using such a system was aligned with the author's experience and ambition, offering not only a vehicle for development but also dissemination and participation. The benefits of structuring, semantic tagging, work-flow, language translation, accessibility, visual design and multimedia features of the Plone CMS were seen as appropriate for the task based on experience using this CMS for the websites of key relevant professional organisations in recent years - Ultralab, Core Education UK and the National Archive of Educational Computing. These methods match digitally the way in which many dissertation writers will adopt a paper filing system using boxes, but permits greater flexibility of organisation and the potential for searching and sorting the data generated as the process unfolded. It ultimately offered me, as a designer of digital artefacts, the opportunity to use my online design knowledge and capacity to solve a challenging data handling problem as described in the following sections.

Gathering the evidence of practice

The first step was to enter the events in my practice using the 'Event' content type in Plone and collecting these in the Portfolio section. Each event consisted of a title, summary, description, start and end date for each of the elements of my practice. I chose to be broad in scope, creating an auto-biographical account which is more complete than required for this dissertation, but allowed decisions on relevance, importance and contribution to made through a second pass. An important consequence of this process was the positive effect of building a rounded account of my life experience leading to a holistic picture. The outcome is a list of around 400 items of practice.

Categorising the evidence

Each entry was tagged as belonging to one of seven categories that emerged from considering the kinds of practice I had engaged in:

- education - events in my formal lifelong education;

- employment - posts held;

- project - research and development projects undertaken;

- professional - positions of professional activity, e.g. societies, examination, advice;

- conference - participation in conferences;

- publication - papers and other media published formally;

- teaching - activity where my rôle was to teach others.

Adding reflections on practice and selecting key contributions to knowledge

To create a manageable portfolio for assessment of this dissertation, a selection of events was made that seemed to offer potential for the development of a doctoral thesis through a process of reflection (Dewey 1933, Schön 1983), following the requirements for this kind of PhD. These events were edited to include a paragraph or more of reflective writing, identifying the key elements within them that influenced the development of my design practice and assessing the contribution made by me in what were frequently collaborative activities. As well as clarifying the nature of my contribution, I assessed the proportion of it by recalling the size of the team I worked with, the role I was playing and the quality of my involvement. This was reduced to a single percentage value (as the regulation expected) and then verified by consultation with the key team member.

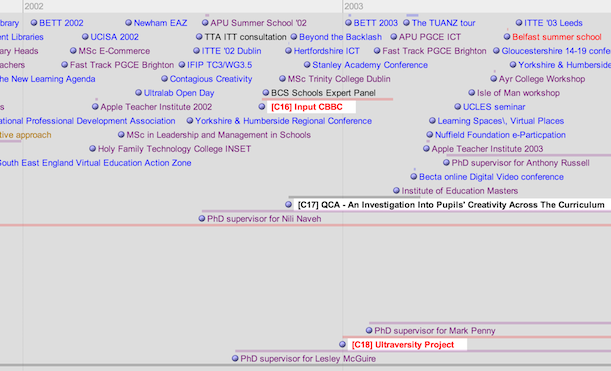

From these items, a further selection was made to shorten the list to form the basis of a claim for examination. These items are tagged 'claim' and show with a white background and bold text in the portfolio timeline as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Claim items highlighted in white on a timeline of my professional practice

" iv. Where any work has been published or carried out in collaboration with other persons, a statement signed by the candidate and co-authors or collaborators specifying the extent of the relative contributions of each to the work. (Note: the University reserves the right to consult with any of the co-authors or collaborators in respect of this statement)."

(Regulations and Procedures Governing the Award of the Degrees of: Doctor of Philosophy by Published Work and Doctor of Philosophy by Practice Approved by the Board of Studies for Research Degrees

Approved by the Academic Board, October 2008 Version 3 p5)

I was conscious of the limitations of such an approach in terms of my bias, and so deliberately determined a percentage contribution as low as seemed reasonable to me, for example usually not exceeding an equal contribution based on the number of members in the team and sometimes lower.

On reflection, I consider the requirement to estimate my contribution in percentage terms to be too limited, and in future would propose the regulations change to use more qualitative terms ranked as:

- leader;

- one of a pair;

- member of small team;

- critical friend and

- member of large team.

Identifying originality, impact and importance in practice

A final process of identifying the originality, impact and importance of the items of practice on which I based the claim was undertaken and referenced to evidence to corroborate my judgement. In some cases the practice was very public and on the large (national and international) scale and may be readily judged for these factors by other academics and practitioners in the field.

The outcome of this process forms the basis of the Claim made in that section of this dissertation.

(Words: 2039 )