Research approaches

Approach to Practice

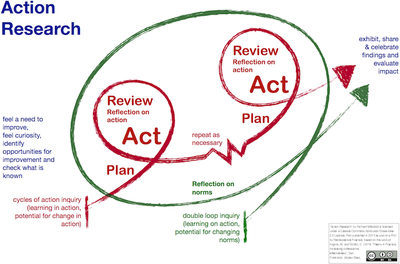

The design of software, resources and systems I have developed has been undertaken in the context of a series of research projects. The inquiry paradigm of these projects started with creative curriculum development in the early part of my career and later became overlaid with a more explicitly collaborative action research approach (Lewin 1973, 205-6; Argyris and Schön 1978), within and on the education system itself. My mature visualisation of this approach is shown in the following figure, developed as a wall poster:

Figure 2: A model of action research

This paradigm is not without its problems, as Somekh and Zeichner put it:

Action research, as a proposition, has discursive power because it embodies a collision of terms. In generating research knowledge and improving social action at the same time, action research challenges the normative values of two distinct ways of being – that of the scholar and the activist.

(Somekh & Zeichner 2009, p5)

This notion of two ways of being has specific attraction for the designer & developer in me, who loves to make and do, not simply think and reflect. Thus it has been natural for me to engage in the iterative and cyclical phases of action research - planning, acting, reviewing and with growing awareness of its meaning. Planning has included collaboration with experts, practitioners and learners inspired to envision the potential for innovation with technology in education. Acting has ranged from coding programs, creating CD-ROMs, designing web-sites, configuring online communities, teaching, facilitation, marketing of courses and direction of large teams of colleagues. Reviewing has involved empirical data collection methods including observation, interview, focus group, survey and videography. This has been followed by analysis of the quantitative & qualitative data collected and subsequent interpretation to develop conclusions which inform the next cycle of inquiry. Double loop learning, the identification and critical questioning of governing variables, has been common throughout as I and collaborators bloodied ourselves confronting the inherent conservatism of educational practices, institutions and frameworks whilst making sense of technology innovations.

This action research approach and all these methods have been employed in my practice as part of the many research and development projects undertaken, and they are described and exemplified in the section Methodologies in Practice.

Approach to Thesis

When setting out to develop this thesis, I decided on a reflective methodological approach and related methods to construct it, but, keeping true to my practice of design and what drives me, the design and development of a resource in the shape of a web site was a vital element. The steps taken to arrive at the substance and presentation of my thesis are discussed in the section Methodology for this thesis.

This web-site can be found at http://phd.richardmillwood.net

Values

The research and development I have been engaged in has always been values-driven, in a nutshell 'to change the world for the better'. Over time these values have developed, but they clearly indicate a subjective viewpoint, and thus run the risk of introducing bias and overlooking issues. The approach has been to recognise these values, identify the risks and maintain the moral perspective.

The most important of these values are discussed below.

Collaboration

All the research and development I have engaged in recognises that collaboration is essential. The positive features for me are:

- a continuing dialogue of critical friendship;

- the benefit of diverse strengths and perspectives;

- where possible, the democratic involvement of beneficiaries and stakeholders to improve ideas, evaluation and uptake.

The price on occasion has been an 'averaging' of creative ideas to achieve consensus, but on reflecting back over this work, this has rarely prevented innovation.

Social justice

The idea that research and development might address inequalities of opportunity in society through education has been central. This means that methodologies such as experimental design, which favour one group over another through a treatment group and a control group, have been avoided in the work I have undertaken, and more naturalistic and qualitative methods used to evaluate outcomes. In the design process it has meant paying attention to diversity, culture and gender issues and making positive efforts in the design of innovations to address these. This has occasionally needed to counter technology-led innovation, which so often simply addresses 'normal' users. In some cases, a compromise has been needed between exploring new designs and addressing accessibility, whilst maintaining a critical view of the issue.

Transparency and participation

My first software development work as a full-time researcher at Computers in the Curriculum in 1980 obliged me to work closely and to be led in pedagogical issues by teacher-groups and individual teachers leading on items of software. This demanded a transparency in planning and participation in design which I came to value. The returns were a growing awareness of practising teachers' knowledge and concerns combined with a practical means to deliver on the values of social justice. This in turn led to design and development criteria informed by my practice working with the teachers. In later projects, especially at Ultralab in the 90s this approach was extended to include school students as 'co-researchers', inviting them to understand the goals of our developments and to contribute at every level.

Delight

The idea that delight was essential to successful learning was a central tenet in Ultralab in the 90s, permitting us to develop software for learning with features intended to inspire delight in learners. But it wasn't until 2006 that I realised how much tacit knowledge had been developed. The opportunity to articulate this fully for Teachers' TV's School Matters series, Happiest Days? (Millwood 2007) and for a poster An Analysis of Delight (Millwood 2010) helped me to recognise the nuanced detail of this concept and how deeply it had become key to my design and development. The influence of David Hargreaves (1975) in his book Interpersonal Relations and Education and John Heron in his Feeling and Personhood: Psychology in Another Key (1992) has been central to developing this concept of delight.

(Words: 1116 )