Research approaches

Research approach developed in practice

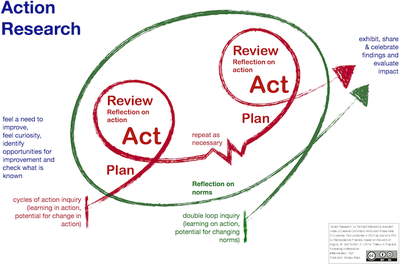

The design of software, resources and systems I have developed has been undertaken in the context of a series of research projects. The inquiry paradigm of these projects started with creative curriculum development in the early part of my career and later became overlaid with a more explicitly collaborative action research approach (Lewin 1973, 205-6; Argyris and Schön 1978), within and on the education system itself. My mature visualisation of this approach is shown in the following figure, developed as a wall poster:

Figure 2: A model of action research

This paradigm is not without its problems, as Somekh and Zeichner put it:

Action research, as a proposition, has discursive power because it embodies a collision of terms. In generating research knowledge and improving social action at the same time, action research challenges the normative values of two distinct ways of being – that of the scholar and the activist.

(Somekh & Zeichner 2009, p5)

This notion of two ways of being has specific attraction for the designer & developer in me, who loves to make and do, not simply think and reflect. Thus it has been natural for me to engage in the iterative and cyclical phases of action research - planning, acting, reviewing and with growing awareness of its meaning. Planning has included collaboration with experts, practitioners and learners inspired to envision the potential for innovation with technology in education. Acting has ranged from coding programs, creating CD-ROMs, designing web-sites, configuring online communities, teaching, facilitation, marketing of courses and direction of large teams of colleagues. Reviewing has involved empirical data collection methods including observation, interview, focus group, survey and videography. This has been followed by analysis of the quantitative & qualitative data collected and subsequent interpretation to develop conclusions which inform the next cycle of inquiry. Double loop learning, the identification and critical questioning of governing variables (Argyris and Schön 1978), has been common throughout as I and collaborators bloodied ourselves confronting the inherent conservatism of educational practices, institutions and frameworks whilst making sense of technology innovations.

This action research approach and all these methods have been employed in my practice as part of the many research and development projects undertaken, and they are described and exemplified in the section Methodologies developed in Practice.

Research approach to the dissertation

When setting out to develop this dissertation, I decided on a reflective methodological approach (Dewey 1933, Schön 1983) and related methods to construct it, but, keeping true to my practice of design and what drives me, the design and development of a resource in the shape of a web site was a vital element. The steps taken to arrive at the substance and presentation of my dissertation are discussed in the section Methodology for this dissertation.

This web-site can be found at http://phd.richardmillwood.net

Values driving the research

The research and development I have been engaged in has always been values-driven, in a nutshell 'to change the world for the better'. Over time these values have developed, but they clearly indicate a subjective viewpoint, and thus run the risk of introducing bias and overlooking issues. Friedman et al explain that the motivation for such values cannot be purely empirical:

"values cannot be motivated only by an empirical account of the external world, but depend substantively on the interests and desires of human beings within a cultural milieu"

(Friedman et al 2006, 2)

Friedman et al explain the background to a values-based approach (Friedman et al 2006, 2) and then go on to exemplify these, see table 2: Human Values (with Ethical Import) Often Implicated in System Design (Friedman et al 2006, 17). These tend towards individual rights of users rather than responsibilities, in a context of designers and users. The authors also note that the set is not comprehensive.

Table 2: Human Values (with Ethical Import) Often Implicated in System Design

|

Human Value |

Definition |

|

Human Welfare |

Refers to people's physical, material, and psychological well-being |

|

Ownership and Property |

Refers to a right to possess an object (or information), use it, manage it, derive income from it, and bequeath it |

|

Privacy |

Refers to a claim, an entitlement, or a right of an individual to determine what information about himself or herself can be communicated to others |

|

Freedom From Bias |

Refers to systematic unfairness perpetrated on individuals or groups, including pre-existing social bias, technical bias, and emergent social bias |

|

Universal Usability |

Refers to making all people successful users of information technology |

|

Trust |

Refers to expectations that exist between people who can experience good will, extend good will toward others, feel vulnerable, and experience betrayal |

|

Autonomy |

Refers to people's ability to decide, plan, and act in ways that they believe will help them to achieve their goals |

|

Informed Consent |

Refers to garnering people's agreement, encompassing criteria of disclosure and comprehension (for 'informed') and voluntariness, competence, and agreement (for 'consent') |

|

Accountability |

Refers to the properties that ensures that the actions of a person, people, or institution may be traced uniquely to the person, people, or institution |

|

Courtesy |

Refers to treating people with politeness and consideration |

|

Identity |

Refers to people's understanding of who they are over time, embracing both continuity and discontinuity over time |

|

Calmness |

Refers to a peaceful and composed psychological state |

|

Environmental Sustainability |

Refers to sustaining ecosystems such that they meet the needs of the present without compromising future generations |

The values I identified diverge and are a subset of theirs, and focus on responsibilities on both designers and users as partners in design.

The approach I have taken here has been to identify the key values that have driven my work, critically recognise the risks whilst maintaining a moral & ethical perspective and where possible, make a connection with Friedman et al's set .

Collaboration

This value is related to Friedman et al's 'Trust' and 'Autonomy'. All the research and development I have engaged in recognises that collaboration is essential. The positive features for me are:

- a continuing dialogue of critical friendship;

- the benefit of diverse strengths and perspectives;

- where possible, the democratic involvement of beneficiaries and stakeholders to improve ideas, evaluation and uptake.

This follows the approach of Cooperative Inquiry (Heron and Reason 2006, 144-152) which recognises an approach where people with similar concerns work together to make sense of their world, developing creative ways of considering problems and learning how to bring about change in things that they want to improve.

Heron and Reason (ibid.) identify two participatory principles:

- epistemic participation, “propositional knowledge that is the outcome of the research is grounded by the researchers in their own experiential knowledge”; and

- political participation, “research subjects have the basic human right to participate fully in designing the research that intends to gather knowledge about them.”

This approach rejects the division of practitioner and researcher into different roles. Instead, it sees inquiry as a social process that is emancipatory, in that allows those who participate to be considered both as researchers and as themselves.

Boylorn (2008) identifies:

Participants as co-researchers refers to a participatory method of research that situates participants as joint contributors and investigators to the findings of a research project. This qualitative research approach validates and privileges the experiences of participants, making them experts and therefore co-researchers and collaborators in the process of gathering and interpreting data.

(Boylorn 2008)

One risk has been an 'averaging' of creative ideas to achieve consensus, but on reflecting back over my practice, this has rarely prevented innovation. Another relates to the relative lack of expertise, which may limit the participant's ability to contribute. This is particularly so when working with students, but the benefits can be unexpected. With higher expectations, young people often step up to meet them, as discovered in the context of the [P6] Étui project, where we invited children to act as researchers to evaluate toys and their design.

Critical friendship in research

This is related to Friedman et al's Freedom from bias'. It has been vital throughout my practice to invite colleagues to comment on plans, activity and analysis.

Costa and Kallick (1993) define a critical friend as:

a trusted person who asks provocative questions, provides data to be examined through another lens, and offers critiques of a person’s work as a friend. A critical friend takes the time to fully understand the context of the work presented and the outcomes that the person or group is working toward. The friend is an advocate for the success of that work.

(Costa and Kallick 1993)

I have valued many critical friends, listed in the Portfolio and acting as a critical friend to many colleagues, and so this has been an important value in my practice.

The risks include the potential for breakdown of relationship and trust, as Cost and Kallick (1993) put it:

Because the concept of critique often carries negative baggage, a critical friendship requires trust and a formal process. Many people equate critique with judgment, and when someone offers criticism, they brace themselves for negative comments.

(Costa and Kallick 1993)

Social justice

This is related to Friedman et al's 'Freedom from bias'. The idea that research and development might address inequalities of opportunity in society through education has been central to my practice. I have tried to follow Light and Luckin's (2008) proposal that we :

address the way in which TEL and user-centred design approaches can offer learners an experience that meets their individual needs and addresses the needs of minority groups as well as the majority

(Light and Luckin 2008, 30)

Thus I have avoided methodologies such as experimental design, which favour one group over another through a treatment group and a control group and to favour more participative and naturalistic approaches using qualitative methods to evaluate outcomes. In the design process it has meant paying attention to diversity, culture and gender issues and making positive efforts in the design of innovations to address these. This has occasionally needed to counter technology-led innovation, which so often simply addresses 'normal' users.

The risk is that in some cases, a compromise has been needed between exploring new designs and addressing accessibility, whilst maintaining a moral and ethical view of the issue.

Transparency and participation

This could be the opposite of Friedman et al's 'Privacy'. My first software development work as a full-time researcher at Computers in the Curriculum in 1980 obliged me to work closely and to be led in pedagogical issues by teacher-groups and individual teachers leading on items of software. This demanded a transparency in planning and participation in design which I came to value. The returns were a growing awareness of practising teachers' knowledge and concerns combined with a practical means to deliver on the values of social justice. This in turn led to design and development criteria informed by my practice working with the teachers. In later projects, especially at Ultralab in the 90s this approach was extended to include school students as 'co-researchers', inviting them to understand the goals of our developments and to contribute at every level.

The risks relate to privacy and safety for participants, which can be undermined with too much transparency.

Delight

There is no equivalent to delight in Friedman et al's analysis. The intuitive idea that delight was essential to successful learning was a central tenet in Ultralab in the 90s, encouraging the team to develop software for learning with features intended to inspire delight in learners. Hargreaves analysis of teacher types as 'lion-tamer', 'entertainer' and 'new romantic' (Hargreaves 1992, 163) had prepared me for considering the affective nature of learning, but it wasn't until 2006 that I realised how much tacit knowledge had been developed by myself and colleagues to support delight as a value in design. The demands of articulating this fully in developing and presenting a television programme on well-being in schools for the Teachers' TV's School Matters series (Millwood 2007), helped me to recognise the nuanced detail of the concept and how deeply it had become key to my design and development practice. John Heron (Heron 1992, 122) theorises that delight may be experienced in multiple ways: 'appreciation' arising from a love of aesthetic form, 'interest' from a love of knowledge and 'zest' from a love of action. These delights are individual in nature, so I extended this analysis (Millwood 2008a) to propose three delights that are derived in association with other people: 'conviviality' from a love of company, 'recognition' from the love of achievement and 'controversy' from a love of dissent. All six of these delights have become important guides to effectiveness in my practice of designing educational experiences.

The risks in this value relate mostly to the diminution of delight and its confusion with 'fun', so often considered to be in opposition to the hard work that learning demands and thus a distraction.

Ethical issues

With the breadth of research & development undertaken throughout my practice, there have been a full range of ethical issues confronted. Particularly relevant have been issues of privacy and data protection with regard to minors, particularly as we developed large scale action research with school-aged children and in online environments. Measures to ensure appropriate ethical practice in the projects undertaken have been dealt with through the arrangements in place with my employers, the participants and their host organisations where relevant, but in some cases these had to be developed further in the context of new risks posed by the use of online technology and visual media.

In developing this dissertation, the main ethical concern has been to obtain the informed consent of colleagues I have described in the Portfolio. This has been done through invitation to review the materials and respond - all those who are still living have been kind enough to provide that. It has been essential to write about others, even though this dissertation is about my thesis and my practice, since:

writing the Self without acknowledging the Other is itself a violent (symbolic) act against the ethical condition that comes with being human.

(Roth 2009)

Thus, since so much of the practice I have engaged in has involved collaboration, it would be ethically unreasonable not to explain others' contribution to the thesis outlined in this dissertation.

(Words: 2948 )